This month we are featuring Allen Hirsch for the Capitol Hill Art League’s Mind of the Artist series. Read Allen’s story and check out his artwork below.

You can view more of Allen’s artwork here:

Which came first in your life, the science or the art?

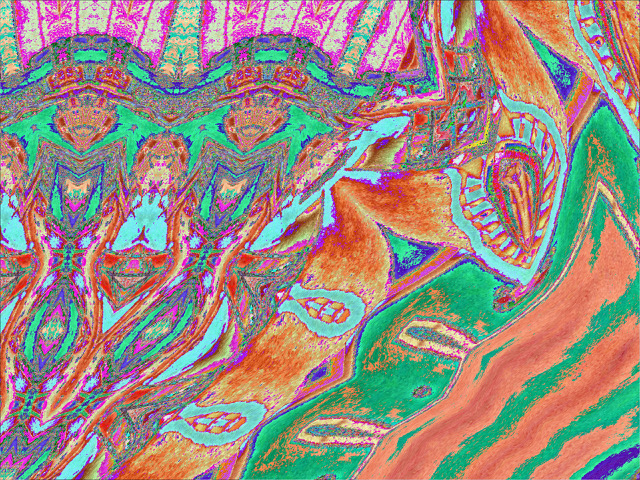

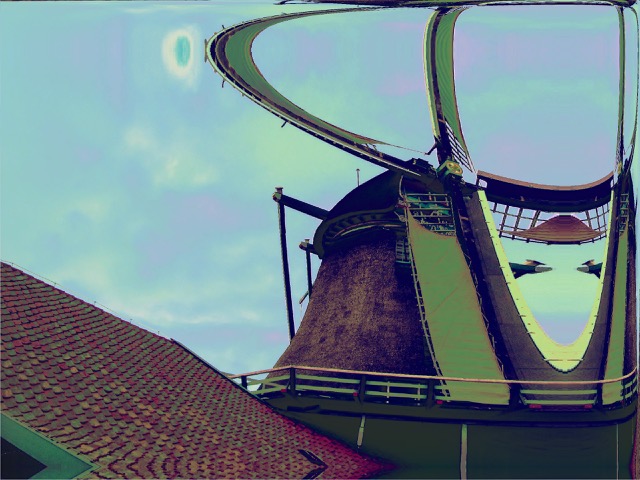

My interest in being an artist comes from growing up in a close-knit community in Central New Jersey in the early 1950s as the son of Jewish chicken farmers turned landscapers. My parents’ switch to horticulture was a true gift to me, nurturing a fascination with exotic plants and gardens beginning in my elementary school years, an attachment that has remained with me to this day. Indeed, it is photographic images of the plants that I grew in my own exotic garden that serve as the basis for much of my digital art. I genuinely love to look at and cultivate plants and admire their beauty, but even as a very young person I was drawn to science. Today, I am still a practicing biophysicist marketing chromatography technology I co-invented, but I have also developed as a mathematical artist due to a seminal family tie. My late brother Gene was a classically trained artist in oils and watercolors, and by the late 80s he had also become a digital artist, using available tools such as Photoshop and Painter to create elegant representational paintings from photographs. When our first child came in 1992, he urged me to try fractal style painting with the computer because I am good at math and he said it might relax me. Up to that point I, like many biologists, was an indifferent computer programmer. Now I had a second chance, and I dived into learning proper structured programming by initially building screen saver painting programs. I soon switched to working every night on digital imaging problems my brother gave me, until finally I turned exclusively to scientific programming at the turn of the century, and this focus on computer programming proved invaluable to my professional scientific work. Yet in the years since, slowly cooking in my subconscious was a scheme for a very large and complex color and space manipulation engine. It took me years to finally sit down and write the code, and I am continually expanding it, but it has been fully operational for seven years, allowing me to create a wide array of representational, impressionist, surreal and abstract images purely through the use of mathematics.

What materials do you use to create your artworks?

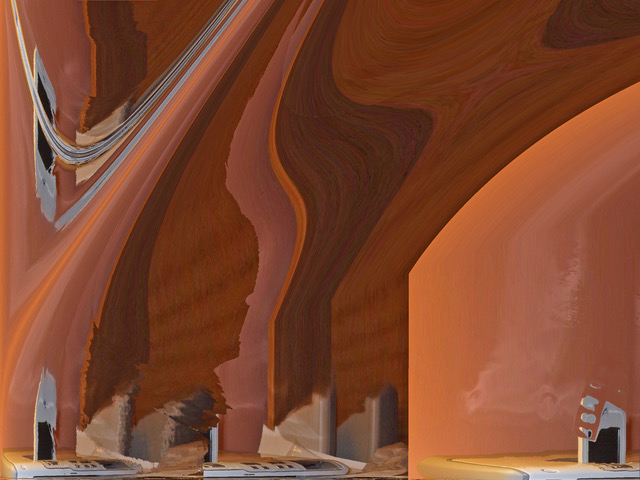

All of the software used to create my images has been created by me, including the resize software that allows me to print very large format images with exquisite fidelity (I have patented the resize software). The software is a mathematical painting engine that I control through a GUI. What the software is actually doing under my direction can be envisioned accurately as follows. Imagine an image made of wet paint (in my program this is either a digital photograph or previously transformed image or hybrids thereof). The artist takes a brush and begins to swirl the paint around or takes a dab of paint from one part of the image and transfers it to another part. Now imagine that the tip of the brush is so fine and the image is discerned at the microscopic level such that the artist can control the movement of each individual dye element in the paint (each pixel in a digital image). Finally, imagine that the movement of the brush holding each dye element is controlled by complex patterning strategies the artist conceives. That is very close to what I do with my main engine. After each element is algorithmically moved to its new location a second mathematical transformation of the element’s colors can also be simultaneously initiated if I so choose as I set up the painting run. Because I can control the parameters in the equations to one part in a billion billion, I can manipulate my images with great precision and can systematically alter the images to try to achieve an acceptable esthetic. In addition, a separate part of my system allows me to do extremely complex color transformations on each pixel using mathematical transformations of the colors in the pixels immediately surrounding it. This allows me to expose amazing hidden patterns even in unremarkable images.

Artwork/Exhibition you are most proud of:

My inventory is enormous because my program is extremely efficient. At this time I have somewhere near 130,000 paintings. Thus, I have too many “favorites” to know where to begin. I think my best exhibitions have been the first and third at ArtSeen Gallery. The Gene Davis Inspiration show that I hung at Artists and Makers was reviewed favorably by Mark Jenkins in the Post.

Which artists inspire and/or have influenced you?

I especially love several of the early pioneers of modern art. My favorite is Monet, and I am also very fond of Mondrian, Kandinsky, Picasso, Klee, Klimt, Renoir, Van Gogh and Miro to name just a few. But my late brother Gene is by far my greatest artistic influence. On Instagram and in museums and galleries I frequently contemporary work that I find immensely fascinating

Is there anything else you want to tell us

It seems odd to me that photography is widely and properly considered a legitimate art form, but digital art struggles for similar respect. I think part of the answer lies in the perception of the talent necessary to produce the image. Most of us who have taken many photographs in our time on this planet have come to deeply respect those folks who can habitually snatch remarkable photos from the ether. In contrast, using sophisticated filters such as those in Photoshop® and Painter® allows a skilled digital artist to turn mediocre photographs or even blank canvasses into wonderful digital paintings, but it can be argued that it also allows undistinguished talents to produce passable work. Thus, for many it is easy to dismiss the tools of digital art as some sort of giant kaleidoscope. I should elaborate in my particular case. The painting engine I have created is powerful enough to generate fascinating images from a wide range of mathematical inputs and I cannot escape my belief that with a modest amount of training most educated people could rapidly learn to use it effectively. So, the skeptic might say, how artistically deep could such images be, if a huge number of people can master the process? My reply? How many people can master the technical aspects of painting? A very large number as we know, because society is now filled with a vast number of people who have learned how to paint. How many people have mastered the use of a camera? Again, a very large number of people create compelling photographs. So, to me the counter argument seems straightforward: an artist has every legitimate right to master as wide a range of tools as possible, then drive them with wisdom, imagination and originality to create compelling images previously unrealized. The final product is the proper measure of artistic validity-not which tools produced it. This argument requires that one believe that fine tools and no talent will almost always produce mediocre art, but better tools and talent will improve the art. All that being said, the prejudice against digital art is huge and very discouraging to those of us pursuing it with passion.

This is an abbreviated version of an interview from the Art the Science blog for Polyfield Magazine.

IG.: @the_abstract_gardener

Comments are closed